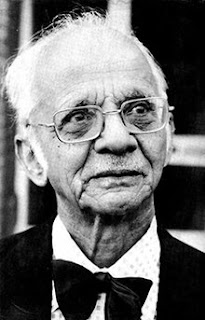

Nirad C Chaudhuri at the opening of the chapter says that he did now not give a good deal of interest to the economic stipulations and issues of England due to the fact he was no longer in a position to recognize them. He is now not only ignorant of the challenge but even contemptuous of it. But at the same time, he stresses the truth that economics as a problem can't be prevented because it has its position in day-to-day human life and plays an important position in deciding the improvement of a country. He points out that he will talk about the Englishman’s relations with money from a moral standpoint.

About the religious practices at home, he has this to say: ‘‘Our religiosity covers every factor of money-making, including the dishonest and violent. There were no more dedicated worshippers of the Goddess Kali than the Thugs.” And in contrast “Christianity does not seem to have been directly involved in financial transactions, and so far, as I have read the Anglican liturgy I do not find in it any reference to money-making although there are prayers for protection against natural calamities.”

He also asserts that in his society money-making is an open

conspiracy, if it is a conspiracy at all. We do not, however, regard it as

such. In his eyes, it is an occupation that can be avowed with pride by every

honest and honorable man. Indeed, as long as we remain in the world we are

expected to put money above everything else.

Chaudhuri failed to see in the Englishman’s mindset to money the sordidness he finds amongst Indians. According to him, it is unthinkable to find in India the smoothness with which English humans put through their economic transactions. They pay their dues immediately and regularly, very readily part with money and without a second’s thought, trust individuals in money matters. All this offers a strong contrast to our society in which Chaudhuri says, the willingness to pay decreases as the ability to pay increases. Chaudhuri used to be exceedingly impressed by the industrial honesty of the English people. They comply with the principle that the love of money, in order to be enjoyed, needs to be restricted. Moreover, the Englishman believes in dwelling in style. He is no longer involved in hoarding money like the Indian.

The author tells

us that spending is the positive urge of the English people. For them spending

is ideal and frugality is the practical correlative of that ideal. But for Indians,

hoarding is a pleasure as well a virtue and spending, a strict duty but

normally a pain. The English always expected to live in style and they were careless

about money.

What excites him

is the fact that the banks and shops are so lenient and honest in cash matters.

Commercial honesty in England amazes him. He calls it a virtue of the highest

order. But English people refrain from all types of ‘shop-talk. But in India

``money-making is an open conspiracy.” In a lighter vein, Nirad Chaudhuri

remarks that money-making is as significant as love-making in the West.

English society

deems it very undignified to openly discuss monetary problems and strategies of

acquisition, a very unusual habit in humans who are described universally as

shopkeepers and capitalistic. But this displays certain negative elements of

the English character. The financial world is truly divided into two: the party

of spenders and the party of savers. The difference is between the misers and

the spendthrifts. But this is the case from the point of the income of view- “...love

for cash in order to be enjoyed need to be restricted”. The scene is one-of-a-kind when it comes to

spending- “On this side, there was as a whole lot assertiveness as there was

once secrecy on the other ''. Nirad Chaudhuri perceives spending to be the

fantastic urge of the English people and saving as a corrective measure. He

offers an insight into the psyche of Indians and the English in relation to

money. For the Indians, hoarding is a pleasure. Unlike the English, we can't spend

money in a planned and deliberate manner. Money is synonymous with temptation,

passion, and panic.

No comments:

Post a Comment